Spanish Motorcycle Diaries - Day 10. From Avila via Valle de los Caidos to Madrid. (29 June 2017)

The first university course I ever took, in 1986 in Berlin, was a history course on the Spanish Civil War. It was taught at Freie Universitaet Berlin by Erich Nolte, (in-)famous in Germany for starting the Historikerstreit in the late 1980s with his theory that National Socialism was a historic response to Bolshevism (and thus possibly a lesser absolute evil, which clearly got minds racing and pens flying). But he piqued my interest in Spain and its fraught 20th century history.

When I learned my first Spanish, during a 2-month intensive course in Madrid in the summer of 1989, when the country had only recently joined the EU and was still poor and underdeveloped, Beata and I had made the effort to travel by public transport some 55km north into the mountains and see the Valle de los Caidos, a huge site in a pine-filled valley which housed the remains of some 34,000 civil war dead, many unidentified, from both sides of the battle. More importantly, however, it was also the site of the biggest concrete cross in the world at over 150m in height, and an underground basilica hewn into the mountain that was of the size of St. Peter in Rome, and which prominently houses two graves: that of Jose Antonio, the founder of the Spanish fascist party, the Falange, and of Francisco Franco, el caudillo, Spain’s rebel army leader and long-time dictator, ruling from 1939 until 1975.

Since coming back to Spain last August, we have been trying to get our minds around the history and identify of this country. Not many countries in Europe deferred dealing with the ideas of the enlightenment until the early 20th century (as the stranglehold of inquisition, traditional catholic education, and backward economics based on unequal land ownership harking back to the days of the Reconquista had done in Spain), then tried to catch up in a short couple of decades, only to see the country torn to bits between the reactionary forces dealing with that spurt of modernity, resulting in a 3-year long destructive civil war from 1936 to 1939 (see The Spanish Holocaust, an objective third-party account published as recently as 2012 by LSE history professor Paul Preston, that describes how Franco slowed down the war so as to exterminate a large part of the opposing political forces), and then one of Europe’s longest and stifling dictatorships until 1975.

Spain can be proud of its historic and bloodless transition to democracy, since Franco had intended for the young Spanish king to continue his autocracy. The ‘transicion’, as it is known in Spain, was bought with one major price: the ‘pacto del olvido’, the pact of forgetting. Spain decided collectively that the young democracy, which only joined the European Union in 1986, could not afford to revisit the historic debates that led to the Civil War, much less commence an open discussion about the merits of Franco’s dictatorship and rule. He was thus allowed to rest in peace, to this day, in the Valle de los Caidos, which he wanted to be as horribly monumental as it strikes you every time you visit it; it was (and astoundingly still is today) part of his legacy. Officially deemed a place of reconciliation due to the 34,000 nameless victims of the civil war buried there, it reeks of self-gratification and self-deification, a monumental shrine to Spanish fascism, to Franco and his legacy. It is also just a stone throw from El Escorial, a huge monastery built by Spanish kings during its ‘siglo de oro’, its golden age, and which serves as burial ground to much royalty – the symbolism of building a mass tomb to yourself and the head of your fascist ideologue adjacent to the Spanish kings and queens was not lost on anybody.

I am neither an architect nor an art historian, but have always taken a strong instinctive disliking to fascist architecture. It usually seeks to make the state and its authority appear unshakable and gigantic, and man (and woman) small and irrelevant. Whether you stand in front of Soviet pieces of grandstanding, or Albert Speer’s project for Berlin under Hitler, or, as in my case at the age of 18, at the footsteps of one of the other major fascist grave sites in Europe, Redipuglia near Trieste in Italy, the effect is the same.

Redipuglia had been commissioned by Mussolini in 1938 to celebrate Italy’s battles during WW1 against the Austro-Hungarian empire, inspired less by its principled stance in the fight between the Entente and the Axis powers, than its Italian Irredentism, its aims to expand its geographical footprints into the Alps (it gained the Trentino and South Tyrol/Alto Adige at the end of WW1) and into neighbouring Dalmatia (today’s Croatia); Italy had signed a secret pact with the Allies in April 1915 promising it those spoils, and entered the war only in that year for these ‘principled’ reasons. The Redipuglia memorial houses the remains of an unthinkable 39,000 identified Italian soldiers and 69,000 unidentified ones, and does so in harrowing architectural fashion that glorifies death and the ultimate sacrifice for the fatherland – a fitting background to Mussolini’s plans in the 1930s to rebuild the Roman Empire around the Mediterranean.

I visited it shortly upon arriving at the UWC of the Adriatic in 1983 as part of a history trip into the battles of WW1 in the area, which had been inept, hugely costly in human terms, and had hardly moved the battle lines over 3 years of at times intense fighting. As in France, the war bogged down into trench warfare quickly, but here was exacerbated by high altitude and winter conditions, making for a horrible toll in futile loss of human lives, including one nearby battle where 11,000 Italians died, 20,000 were wounded, and 265,000 captured (Ernest Hemingway drove an ambulance for the Italian army and fictionalized his impressions in A Farewell to Arms, compulsory reading at UWC Adriatic, before moving on in the 1930s to fight on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War, resulting in his For Whom the Bell Tolls).

What has been striking foreigners in Spain as well as some locals is the oddity that Franco’s grave is still in place there, in a site maintained by the Patrimonio Nacional (something equivalent to the UK National Trust), funded partially by taxpayers money. That on that site there is a Benedictine monastery and boy’s convent school, and that nobody finds it odd that young boys are taught (what?) values there in the proximity of the shrine to one of the longest-ruling dictators and violators of human rights in modern European history. (see Ghosts of Spain by Giles Tremlett, the long-standing Guardian and FT correspondent in Spain, for a good account originally published in 2006 of these contradictions and loose ends in modern Spain).

So of course I wanted to revisit and verify my impressions from 28 years ago, and give Pat a chance to do the same. We came away depressed and harrowed, no surprise. The Christian symbolism utilized to glorify these two men, who caused so much suffering, is overbearing. The biggest cross in the world. A harrowing look on Maria’s face holding Jesus, in grey stone above the basilica’s entrance. Angels that look more like warriors with swords lining the dimly lit underground basilica, which is vast and overpowering. Red and white carnations on the two graves around the altar. Not a single plaque about the 34,000 other dead buried here, no names, no historic exhibition, no attempt at ‘reconciliation’ – mysticism and glory and one inscription in front of the walls where tunnels house the remains of the 34,000 dead: Caidos por dios y por la patria. RIP.

History, it is said, is written by the victors. No different here. The civil war dead did not fight for dios, not the republicans, many of which were communist, socialist, anarchist, and atheist. And Franco and the Falange arguably did not die for la patria either, since they chose to overthrow a validly elected Republican government and impose their will on Spain by force. It is a travesty and misinterpretation of history, and not reconciliation.

There have been many efforts to change things at the Valle. Fascist meetings were forbidden by the Zapatero government in 2009 (they used to meet on 1 Nov, the anniversary of Jose Antonio’s death – shot in 1936 by Republican forces – and Franco’s death on the same day in 1975). A governmental historic commission was appointed in 2011 to deal with the site and the oddity of the government still funding its upkeep. Recently, the opposition PSOE has brought another motion into parliament asking for the removal of Franco’s remains from the site. The last 15 years have seen historic movements and the disinterring of hundreds of civil war victims, brought up from wells and ravines to this day as Spain is now finding the courage to deal with its difficult recent past. Yet the caudillo is still there today. A poster at the entrance to the basilica emphasizes that 90% of the EUR 30m budget come from non-governmental sources. Why it would take EUR 30m of budget to upkeep an old granite hill is another matter.

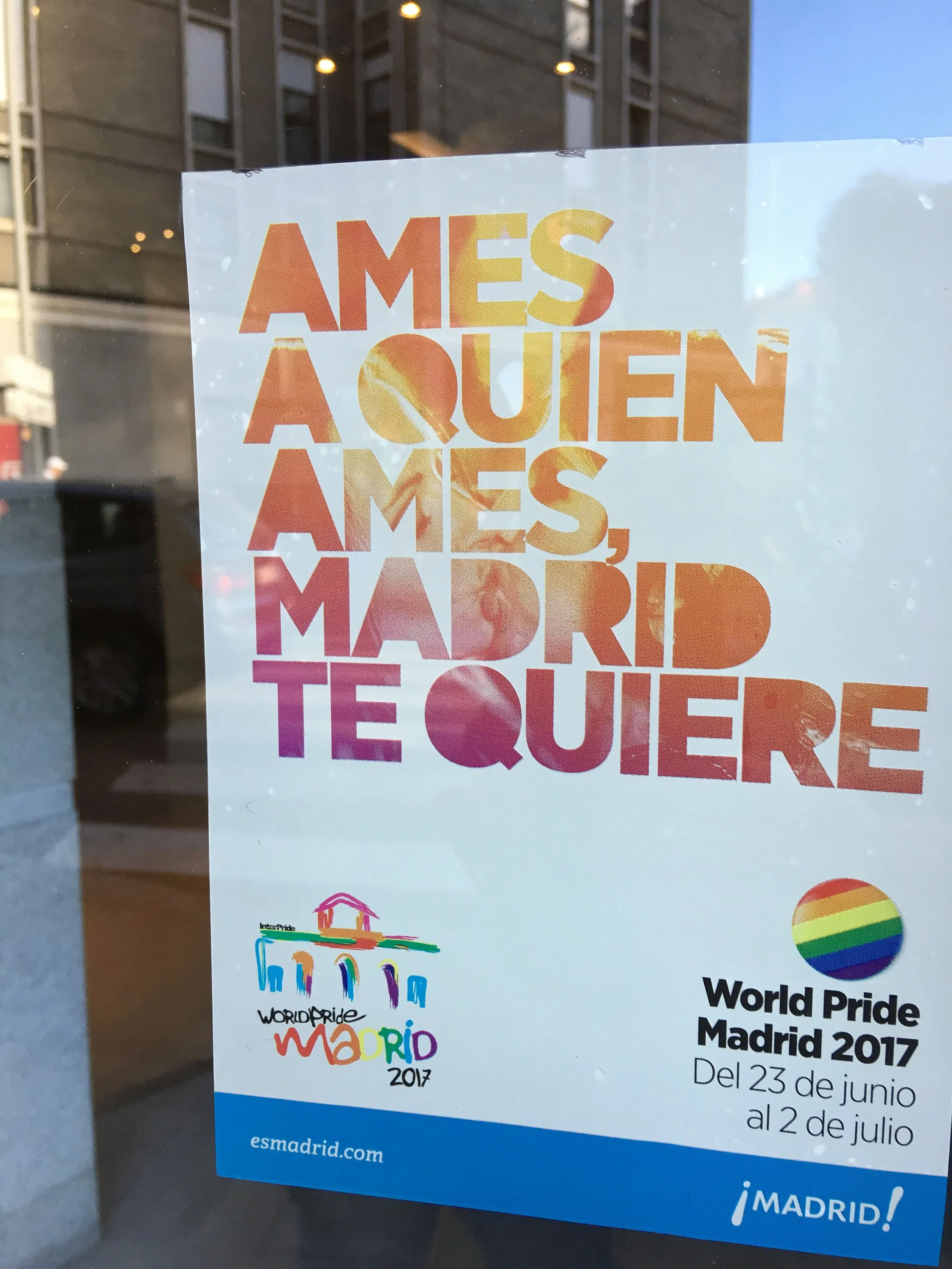

We were happy to turn the Yamaha around and head into gay Madrid. And, irony of it all, Madrid was all decked out in rainbow colours, celebrating LBGT rights. Madrid is the international capital of diversity in 2017, with the wonderful slogan: ‘Ames quien ames, Madrid te quiere’ (Love whom you may, Madrid loves you). The caudillo no doubt would turn in his grave if he knew that his vision of Spain had failed miserably, and the country has rejoined the European family of nations and modernity despite his ghastly efforts to the contrary.

PS: You can form your own view of the Valle at this digital site: https://www.360cities.net/image/benedictine-abbey-of-valle-de-los-caidos-madrid-spain