Riding Northeast from Przemysl via Zamosc to Lublin -- From Austrian Fortress to Lublin Renaissance. (June 7, 2020)

Lublin, June 7

June 4, the day I turn the motorcycle around from course south/south-east towards north/north-east, is a very special day in Polish history. Culminating after decades of protests, of indomination, of not submitting to the Soviet model of economics nor politics nor life, of not accepting the fate ordained by the Allies at Yalta in February 1945 (where both Churchill and Roosevelt underestimated Stalin’s unscrupulous intentions of creating Soviet puppet states in Central Europe, including Poland), free Poland finally wins the day on June 4, 1989, when Solidarnosc’ efforts pay off -- after the Gdansk shipyard protests of summer 1980, suppressed by martial law in December 1981 – roundly winning the first partially free elections, and pushing the imposed socialist totalitarian blueprint onto the ash heap of history, setting Poland on the path to re-joining western Europe and its brethren from the renaissance. And promptly on June 4 the sun comes out and the temperatures move into the mid-20s; Poland’s famed continental climate is back, with its warm, lazy summer evenings inviting one to spend time in its beautiful market squares with a good cold beer.

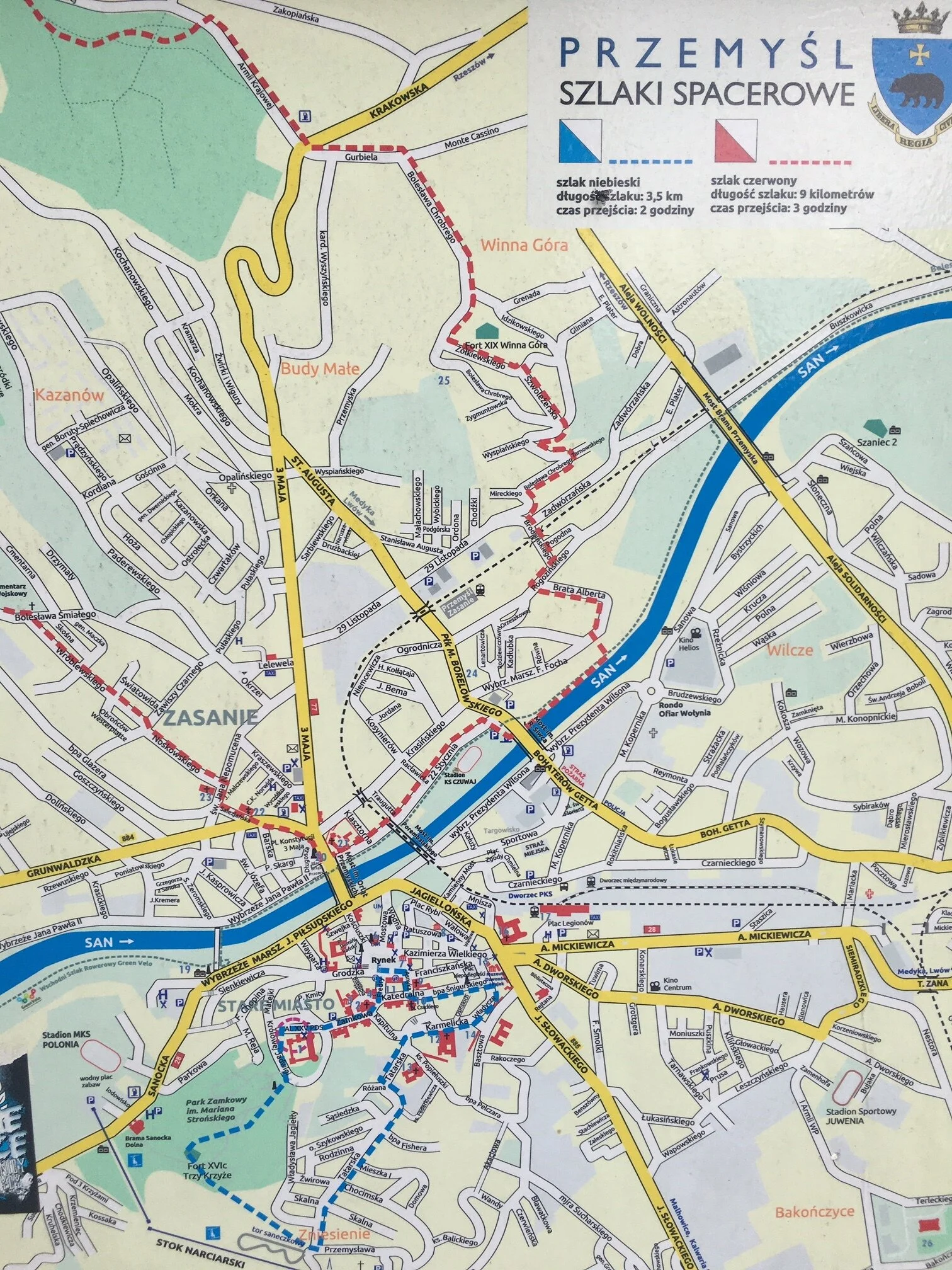

Przemysl, the first stop on my route north (well other than beautiful Krasiczyn castle just above, just outside its city walls), but which is very firmly located in Poland’s SE corner, could have been luckier. It was nearly picked as the capital of Galicia by the Austrians upon the partition of Poland in the last 18th century, but in the end lost out to Lviv (formerly Lwow or Lemberg). It could have had less of a strategic positioning in the SE of the country, a bulwark against potential threats from the SE (Tatars and Turks), or from the east (Russian Empire). But it was turned into one of the most expansive fortresses by the Austrians just before WW1, with some 44 forts placed in a radius of 45km around the town to complement its strong city ramparts – and went on to stop a Russian army of 300,000 in 1914 …. only to fall to the Tsar’s army’s siege in 1915.

Modern Przemysl, which I last visited in 1984 in the depth of the death throes of Polish socialism, when the stores were empty and widespread alcoholism was apparent on the streets as one of the escape routes from an unbearably bleak presence, reminds me of Trieste in the mid-1980s when I went to school in nearby Duino (UWC).

Another marvelous ‘Austrian’ town with many signs of a thriving local economy and architecture around 1900, with a similar ‘fin de siecle’ style to its systemic urban housing and buildings of public importance. But its blossom evidently took place quite a while ago. It is hard for an urban economy to take off when the hinterland is cut off.

Trieste was Austria’s only port on the Mediterranean until WW1, and exhibited that concomitant wealth and confidence and strategic importance in its architecture and swagger; but when post-WW2 the Iron Curtain came down just east of Trieste, the local economy and the city went into a “100 year’s sleep”, only to be kissed awake in 1990 when former Yugoslavia started to integrate back into Europe.

Przemysl shows similar attributes of past grandeur, but its hinterland has also gone missing. One needs to recall that Poland’s eastern border is adjacent to what is arguably Europe’s biggest failed state, a huge country of 55m people that – even before the illegal Russian annexation of Crimea and the Russian undeclared war in eastern Ukraine – was a country whose weak institutions and perennial corruption did not allow it to enjoy its first true period of independence; by most estimates there are more than 2m Ukrainian economic refugees working in Poland today . Add to that, contiguously in the north, the last European Stalinist dictatorship in Belarus under Lukashenko, and you can be forgiven for being surprised how well eastern Poland and its principal cities have done despite carrying all that luggage around with them.

(Not to mention -- which we will leave for a separate blog entry -- that many of the people and peoples that used to make this part of the world a lively polyglot multiethnic melting pot have perished in the Shoah, or been driven away as a result of the two world wars and subsequent forced relocations.)

As I drove around Przemysl, it occurred to me that career choices for young local men in past times would have included working on your father’s farm, in your father’s store, joining a seminar in order to become a priest, or becoming a policeman and soldier to keep all the locals in check and to protect imperial assets in this far-away regional town. And promptly I pass a couple of young priests and then a fully-clad Polish army platoon marching down a street …

At one of the many beautifully restored baroque churches I find a plaque in Polish and Cyrillic … recording how Pope Jan Pawel II, a legendary figure in Poland, in 1991 passed this church back to the Greek Orthodox church in Przymysl -- in these former border lands between Roman Catholicism and Greek Orthodoxy, one geographically never leaves Europe but still regularly comes into contact with a distinctly eastern heritage, including in the spiritual realm. Coming back to the Polish Pope: Mementoes of this irrepressible son of the land who played a key role in fostering the peaceful transition in 1989 pop up in nearly all places; here was a leader with natural authority that is revered to this day in Poland (and who bestowed a legitimacy on the country’s Catholic Church that one cannot help but have second thoughts about in its aping of current administration policy with regard to LGBT and other contentious issues, e.g. regularly attempted further restrictions on what is already one of the tightest abortion regimes in Europe).

I leave out-of-sorts Przemysl and head further northeast, leaving the San river for good, heading for the Bug, which marks Poland’s eastern border for a good stretch. It is one large country, with many stretches full of colourful fields, sparse settlements, rows of birch trees standing guard along adjacent pine forests, excellent EU-co-funded B roads, and some atrocious C roads full of wheel ruts that are fiendishly nerve-racking to navigate on a motorcycle at speed.

And am promptly rewarded by the beauty that is Zamosc. The city is known both as the ‘pearl of the renaissance’ and ‘the Padua of the north’ – and neither are an exaggeration! A smaller town of 60k people today, and less than half that before the Nazis got their fingers on it, it was built over a mere 20 year stretch from 1580, by Bernardo Moreno, an architect from Padua, inspired by its namesake and one of the foremost noblemen of Poland of the time, Jan Zamoyski (great great great ... father of the NY-born historian whose book travels with me on the motorbike). If you read the bio of Zamoyski, what he has achieved in Zamosc comes a little into perspective; here’s an example of how Polish renaissance man, educated and inspired abroad but patriotic and dutiful at home creates a lasting legacy.

As a teen (i.e. in the 1550s), he was sent to serve as page boy at the French Royal Court – and already attended the Sorbonne in his free time. At 19 he went off to the University of Padua in Italy and graduated with a doctorate from there three years later, before returning to Poland (he later became Chancellor and Hetman, i.e. head of the Polish army, amongst other honours).

He conceived of Zamosc together with Paduan architect Moreno. Their concept of creating ‘the ideal city’ based on Italian aesthetic and town-planning principles we had come across in Pienza, a pretty little town enhanced by its native son, Pope Piccolomini, in the Tuscan Val d’Orcia, south of Sienna. It is nonetheless somewhat lesser known to wine connoisseurs than its two neighbouring towns in that marvelous valley of wine and olives and rolling hills, Montepulciano (as in Vino Nobile di M.) and Montalcino (as in Brunello di M.). I had discovered Pienza on another motorcycle excursion some years ago and went on to show it to the family, including its signature dish of pecorino (sheep cheese) topped with honey.

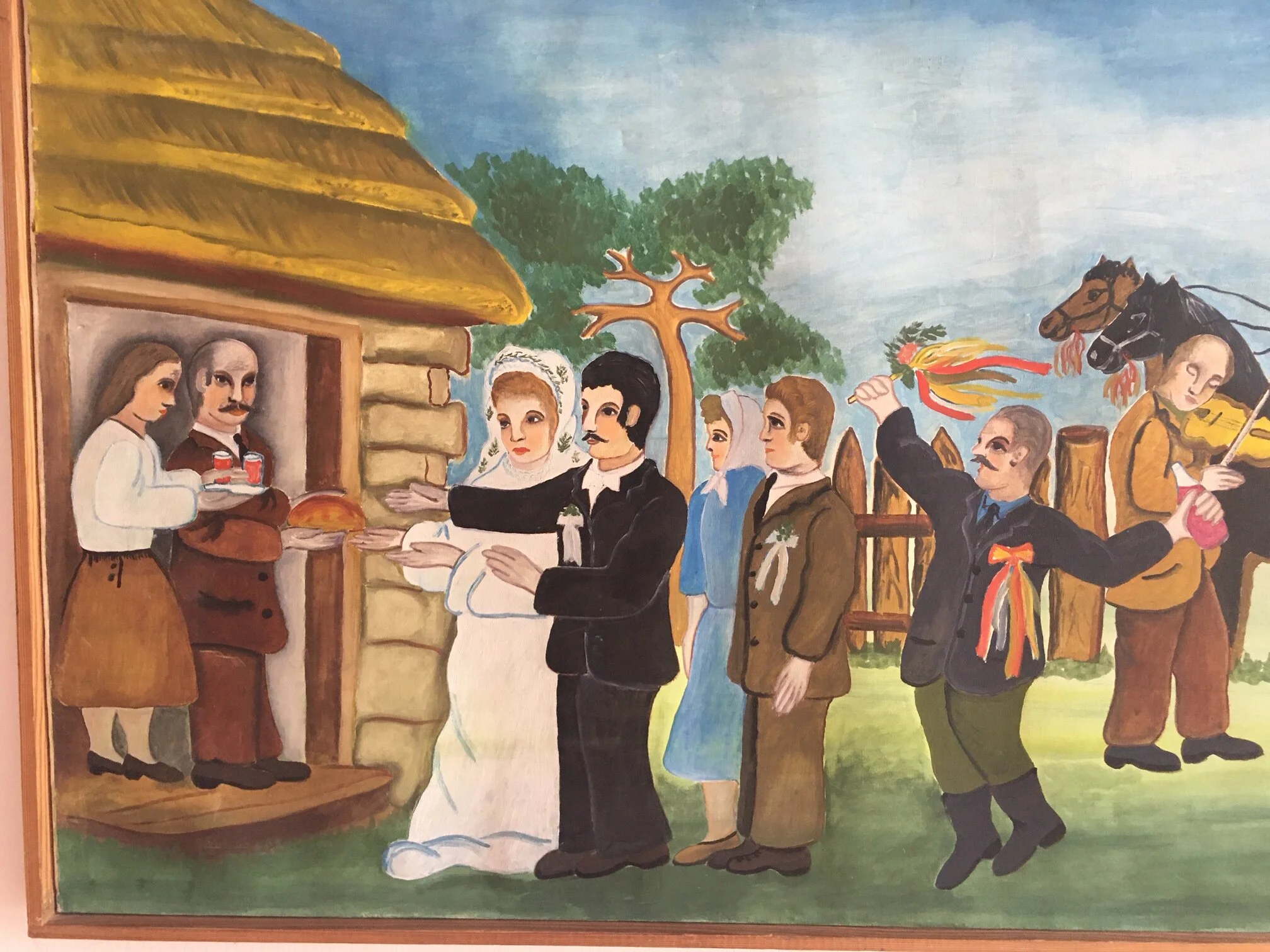

Zamoyski gave settlement and economic rights to Jews and Armenians, both of which created thriving communities alongside Poles and other nationalities in Zamosc. The most beautiful and colourful houses (see pictures below) on the main square, which measures a perfect 100m by 100m, are those of wealthy Armenian traders. Zamoyski’s own palace, like that of the Lubomirski family in Przemysl, today houses a school, befitting his humanist legacy.

The ramparts around the old town were so well designed that they withstood both Cossack and Swedish sieges, and have been beautifully restored (UNESCO declared Zamosc a world heritage site in 1992). Walking into the main square, one does feel like one has just arrived in northern Italy, and not in southeastern Poland. Quite magical indeed. (Until one reads up on the horrors visited upon Zamosc during the 20th century history by Nazi Germany, but we will leave that for later.)

When you leave Zamosc westwards to then loop north towards Lublin, you pass a town that every Polish kid knows … Szczebrzeszyn. The tongue twister that has made the town famous is one that is liable to get even 24 year expats in Warsaw into trouble:

‘W Szczebrzeszynie chrząszcz brzmi w trzcinie’

(It is about some beetle making noises in that little town, if you must know.)

The Lublin of today is the only large Polish town east of the Vistula, and a thriving university town. Like Cracow is known for the Jagiellonian University (founded by Cazimierz the Great), Lublin is known for its KUL, the Catholic University of Lublin, and a center of anti-communist intellectual resistance during the socialist times. Lublin is also home to the Marie Curie-Sklodowska University with another 36,000 students, founded in 1944; if you were not very keen on chemistry like yours truly, you might not recall MCS. However, this Polish scientist is the only woman to win two nobel prizes (Physics in 1903, Chemistry in 1911, the former together with her French husband, the latter for identifying radium and polonium) and the only woman to ever win two nobles in two different fields (as well as the first female professor in Paris). If that were not sufficient, Lublin was also sometimes referred to as ‘the Jewish Oxford’, due to the reputation gained by its yeshiwa (Jewish school of religious learning); in 1567 its headmaster was awarded the title of rector by the Polish king, along with the rights and privileges of other Polish universities.

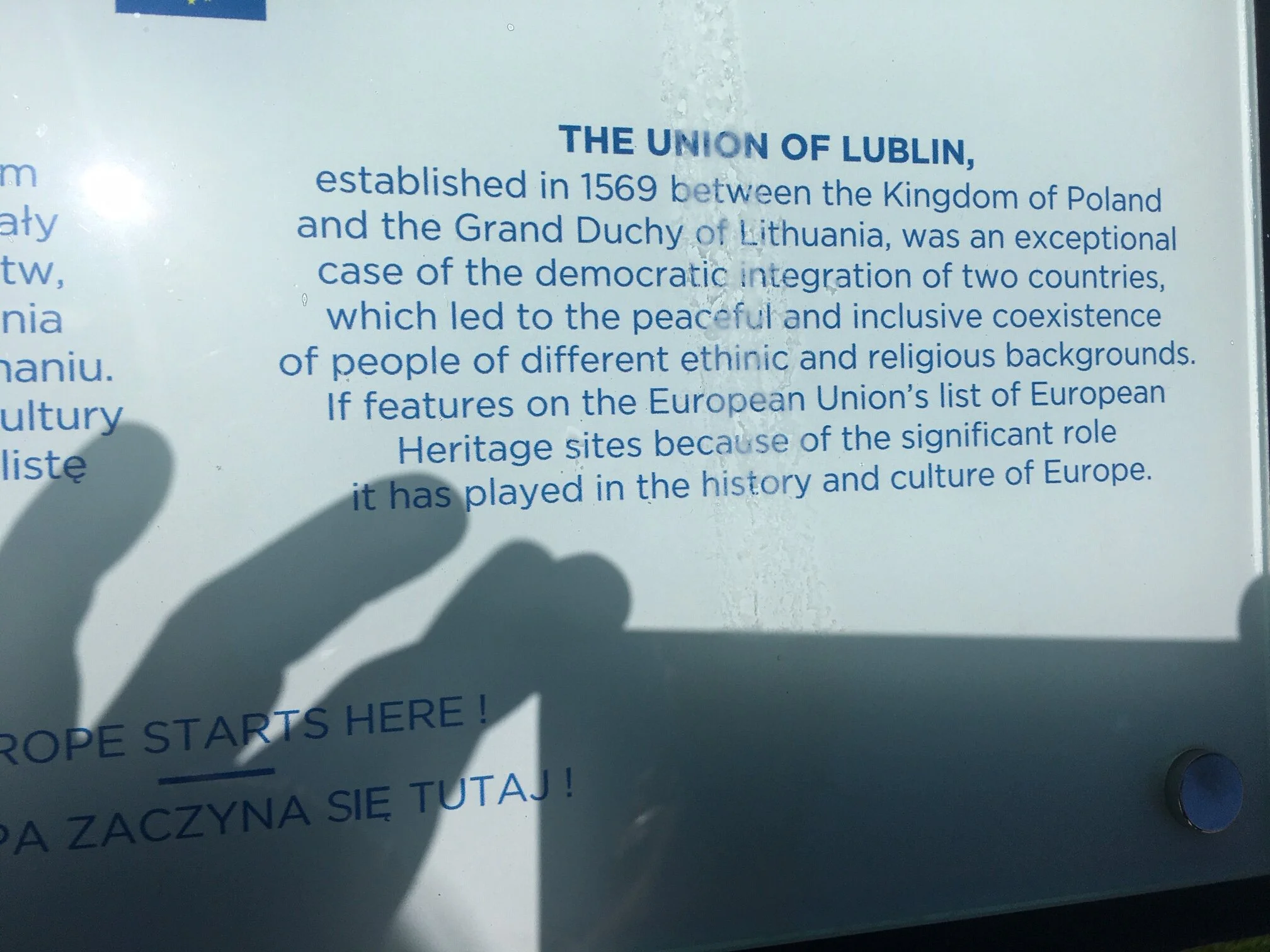

It is also the town in which, 451 years ago (1569), the Union of Lublin between Poland and Lithuania was approved, setting the scene for the successful Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (itself building on the more lose Polish Lithuanian Union of 1385) and a further blossoming of Poland until the Swedish invasion in the mid-17th century. In architecture, there is a distinct style known as Lublin Renaissance, and much of the splendor I witnessed on the trip throughout the southeast and east of the country thus far owes its appeal to this golden age of Poland’s development (in the 16th century).

[There are economists who argue that the last quarter century should be called the ‘New Golden Age’ in Poland; see https://www.lasanozfinance.com/why-poland for some relevant literature.]

Like many successful towns, it had the good fortune to be in the right place and at the right time. Unlike most of Poland’s large cities (Cracow, Warsaw, Wroclaw, Poznan), and most of those on my itinerary so far (Sandomierz, Sanok, Przemysl) it is not situated on a prominent river.

Instead it lies well placed between Cracow, the Polish center of the universe at the time, and Vilnius, the Lithuanian center of the universe at the time, and thus benefitted from the Union voted upon in its walls.

However, as in most Polish towns I visited, beauty and tragedy are close bedfellows. The Lublin castle, founded by – who else – Casimierz the Great, saw its greatest triumph in hosting the assembly of Lithuanian and Polish magnates that approved the aforementioned Union of Lublin in 1569. A plaque outside the castle, located just across from the beautifully restored old town that one reaches via Grodzka or Jewish Gate, mentions that from 1939 the Nazis used the castle as a prison for up to 40,000 Poles, many from the resistance, engaging in widespread torture and murder. When the Soviets took over in 1944, the NKVD (the predecessor to the KGB) used that same castle (prison) to incarcerate up to 32,000 Poles, many associated with the non-communist resistance army (AK), with similar methods to the Nazis … one is simply lost for words … before walking over to the two Jewish cemeteries on the other side of town, and starting to read up on the thriving Jewish community before WW2 …

The Lublin of 2020 emanates coolness and self-confidence. Smart town planning, efficient use of EU funds, a strong educational and cultural legacy, many students, architecturally impressive new cultural and business centres, a certain nonchalance … it could not be further from the depressed town of 1984 that I had visited in a different epoch. Once again, modern Poland surprises positively, once one gets away from the politics.

(PS: My dad used to say ‘you only see what you know about’. Well, I did not know much about this part of the country, but count myself lucky to have four Warsaw friends, KKK&J, who do, and who generously shared what they love and find fascinating in these regions and cities. Much of what I have covered, visited, seen, appreciated, contextualized, is owed to these knowledgeable and enthusiastic travelers – a big thank you!)